And yet, it is being tom-tommed as ‘freedom’ for farmers and ‘self-reliance’ for country!

Subodh Varma

07 Jun 2020

Silently, and in double quick time, changes in laws related to cultivation, sale, stocking and pricing of agricultural produce – food grain, vegetables, etc. – have been proposed and disposed by the Narendra Modi government. Three ordinances relating to these key dimensions were given Presidential assent late on June 5 night, and they came into force “at once”. These were put on the table only last month by the finance minister as part of the so-called stimulus and cleared by the Cabinet only a couple of days ago.

There has been much jubilation in the mainstream media over these far- reaching policy changes, while most political parties, barring the Left, have been silent. It appears as if the government’s propaganda that these will allow farmers to sell their produce “anywhere” and “get best prices”, and that this will lead to all round prosperity, has been swallowed unquestioningly by most middle class.

As far as the farmers themselves are concerned, virtually all their organisations have opposed these wholesale changes. Cunningly brought in when the COVID-19 pandemic is raging in India and people are fighting for their lives, these changes will decisively hand over agricultural production and trade to big companies and traders, and thus, present an imminent danger to food security in a country that has about 200 million hungry people.

Here is what has happened and what it will lead to:

Changes in Essential Commodities Act (ECA)

This law, passed in 1955, empowered the government to lay limits to the amount of foodgrain stocks traders or companies could keep, as also cap the prices that could be asked for. It is being argued that the law was useful when India faced a foodgrain crisis but now that we have bumper harvests and sufficient production, it is useless if not an obstacle.

So, the new ordinance has inserted a sub-section saying that only in extraordinary circumstances like war, famine, natural calamity etc. can the government “regulate the supply of such foodstuffs, including cereals, pulses, potato, onions, edible oilseeds and oil”, and price caps will be triggered only when prices rise by 100% (for horticultural produce) and 50% for other non-perishable items.

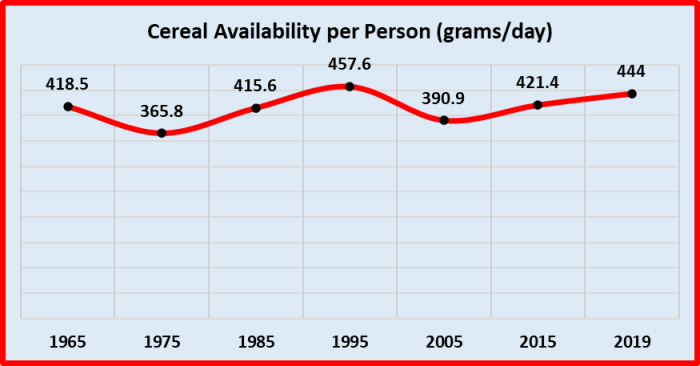

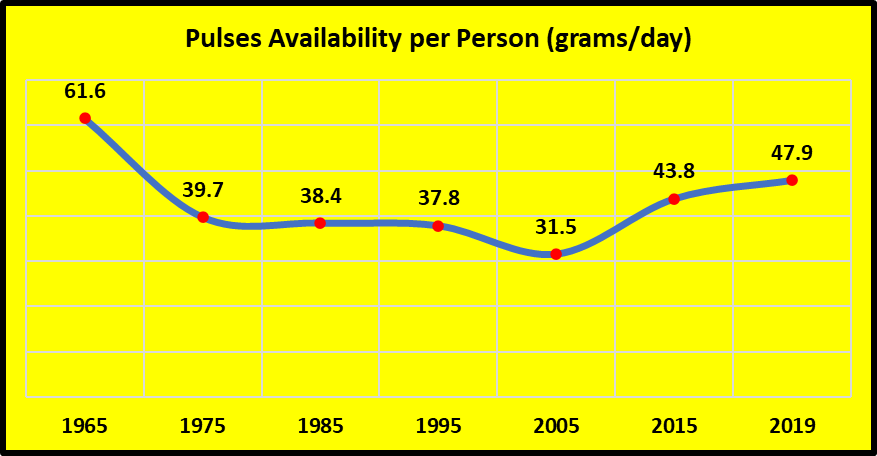

The argument is spurious and patently false. Have a look at the availability of cereals and pulses in the charts below, using data from the government’s own Economic Surveys of different years.

The availability of cereals has been up and down, being determined by monsoons, but between 1965 and 2019, the increase is only about 26 grams per person per day, or 6% of the intake. That’s not enough to feel so confident about, because one bad monsoon will bring it down.

For pulses, the situation has considerably worsened, as can be seen from the chart below. Compared with 1965, people are eating nearly 14 grams less pulses per day – that’s a dip of over 22%. Remember that the availability figures are boosted by huge imports in recent years. If that were to stop, availability would plummet further.

So, removal of stock and price restrictions will mean that big traders (or their cartels) can hoard a lot of stock and thus create scarcity, driving up prices. This is not a far-fetched scenario – it has happened repeatedly with onions even when the ECA was in force. Its “de-fanging”, as some media outlets were gleefully describing it, would be a windfall for monopoly traders and companies who speculate on prices. Profit from hunger.

Scrapping APMC Laws

The second ordinance issued on Friday night scraps the whole existing system of selling and buying agri-produce in India. The Agricultural Produce Market Committees (APMCs) are designated areas created by state governments where various agri-produce can be sold by farmers to licensed persons or commission agents. There were 2,477 principal markets and 4,843 sub-market yards throughout the country.

The purpose of this system was to ensure that greedy and powerful traders do not fleece farmers by paying them lower prices. These markets also became nodes for government procurement of foodgrains. Over the years, considerable corruption entered the system, with agents forming cartels to manipulate prices, or taking bribes to favour selected sellers, etc. However, by doing away with this system altogether, the Modi government has thrown the baby out with the bathwater. Now any trader can approach any farmer anywhere in the country and buy the produce, at whatever price they agree upon.

Since 64% of farmers in the country have small and marginal holdings, and thus will have small quantities of produce to sell, they will hardly be in a position to transport the produce over a long distance to a market/traded which offers a better price. In fact, they will be offered a shortcut by traders who will pick up the produce from them, from the farmgate itself, say. This process will see bigger traders with deeper pockets emerge as winners, swallowing up all the small fry. In these monopolistic conditions, they will also dictate prices and other terms.

Note that APMCs come under state government jurisdiction. But the ordinance specifically over-rides the state laws. The agriculture minister, when asked about this, reportedly claimed that agricultural trade was in the Central List of the Constitution and that is why they could bring this ordinance.

This will dovetail well with the changes in the ECA: traders will be able to hold as much stocks as they want. It will also help big agro-processing companies, including foreign behemoths, to freely buy up foodgrain or even perishables, in pursuit of their own interests. For instance, a biscuit or bread producer will buy up wheat stocks at will and stock them up, disregarding any effect this may have on wheat prices, or on availability of wheat, which is a staple in many parts of the country.

Thus, with this ordinance, the whole system of agri-produce trade has been privatised. The ordinance provides for an elaborate system of legal remedies if payments are not made as per terms. But, will the small farmer take on big companies in court cases that will run for years?

Contract Farming

The third ordinance lays down how farmers can enter into agreements with ‘sponsor parties’ to undertake contract farming, that is, of cultivating and providing certain specified produce in certain quantities, at a fixed price. This system is already in practice in scattered parts of the country. On the face of it, it looks like a beneficial system to farmers because of the promise of a fixed return.

But here are some of the faultlines:

a) prices offered may fall in the future as the sponsor party (usually a big company, often involved in agri-processing) will determine prices based on its own interests;

b) companies will push farmers to produce certain kinds of crops, say, potatoes (for chips) or tomatoes (for ketchup) and any such scaling up will affect the foodgrain output of the country, opening the doors to other companies offering to import the foodgrain. In other words, the country’s food security may be jeopardised;

c) the agreement between farmers and companies will be unequal because the latter have far more resources and power. So, dispute resolution or settling of terms will be very unequal and unjust;

d) Share croppers and other tillers of the soil will get thrown out though the ordinance says they shouldn’t be. The economics will motivate land owners to increase eviction.

e) agricultural workers and their wages or other rights have no place in the new dispensation.

In short, this change also shifts the balance against farmers and towards business houses and big traders, including foreign monopolies.

Seen as a package, the three ordinances thus upturn the present system to install a much more business and trader-friendly system. Neither farmers, agricultural workers, nor the common citizens in India (consumers) stands to benefit from these changes. All these changes do is to open the door to increased profits by agri-traders and agri-processing companies, both domestic and foreign.

This decision also fits in with the Modi government’s overall thrust to privatise everything – from public sector enterprises to healthcare, from education to defence, and from natural resources to space programme. All in the name of building a “self-reliant India”!