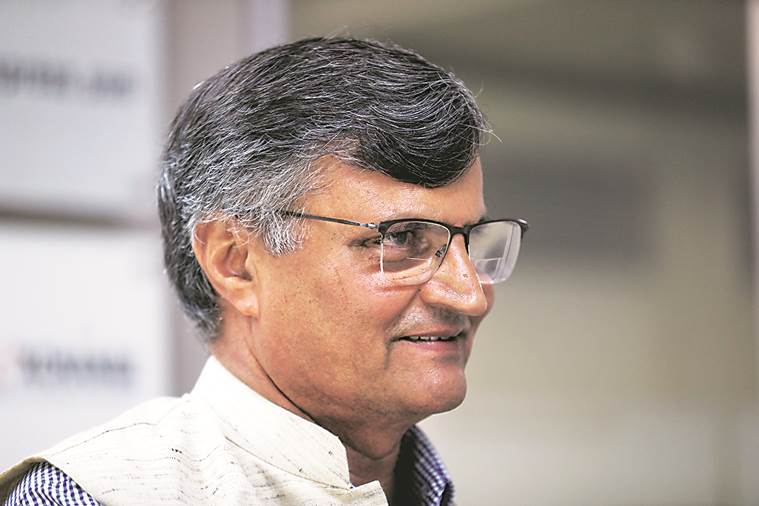

NITI Aayog member Ramesh Chand with National Editor (Rural Affairs and Agriculture) Harish Damodaran at The Indian Express newsroom in Delhi. (Express Photo: Abhinav Saha)

NITI Aayog member Ramesh Chand with National Editor (Rural Affairs and Agriculture) Harish Damodaran at The Indian Express newsroom in Delhi. (Express Photo: Abhinav Saha)

Ramesh Chand, member of the NITI Aayog: Agriculture has been in focus for both positive and negative reasons. “The sector provides livelihood to close to half of India’s population and it is very important for inclusive growth, which also matters for this government’s agenda of Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas. Sometime back, I did a study on how much decline in poverty was witnessed when there was 1% growth in agriculture and 1% growth in non-agriculture. I found that agriculture growth had much more significant impact than non-agriculture growth. We should recognise some of the positive changes that have taken place in the agricultural sector. In the 1970s, we were producing 1 kg of food per person per day — and food here includes not just foodgrains, but also fruits, vegetables, milk etc. At that time, our population was about 56 crore. Now, that has gone up to more than 130 crore, but our per capita food production today is roughly 1.74 kg food per day. This has its own implications, as we are no longer living in scarcity.

Why Ramesh Chand?

A member of the NITI Aayog, Ramesh Chand is seen as key to the Narendra Modi government driving agriculture sector reforms, especially in its second innings. A farm economist of repute, he has been an advocate of dismantling provisions under the Essential Commodities Act and APMC laws that enable restrictions on stockholding, domestic movement and exports, besides preventing large retailers from buying directly from farmers. These views may find resonance in a context where food inflation and shortages have ceased to be a major worry, with the focus now shifting to addressing agrarian distress and doubling farmers’ incomes

HARISH DAMODARAN: Do you think the Narendra Modi government in its first innings was excessively pro-consumer and not pro-producer?

I doubt the government was pro-consumer at the cost of producers. We draw this conclusion only because producer prices have risen at a very low rate after 2014-15, when this government came to power. But agricultural prices historically move in cycles. During 2006 to 2012, there was a sharp increase in global agricultural prices, which fell just around when this government came. In 2012, they were at their peak. But still if one looks at the terms of trade for agriculture — the prices that farmers pay and what prices they receive — these had been improving up to 2015-16. Only in the last two years, the prices paid by farmers have increased at a slightly higher rate compared to the prices received. But overall, the terms of trade figure for 2018-19 is higher than 2011-12… This government has tried hard to keep these prices high with a new formula for fixing MSP (minimum support price) and also through procurement. So it is a combination of factors — international prices, demand and supply cycle — that is responsible for the current agrarian distress. It is very difficult for the government to influence prices beyond a point.

In 2016, the Union government passed an order, after which there are no real restrictions on food commodities with regards to stocking, movement or exports, said Ramesh Chand.

In 2016, the Union government passed an order, after which there are no real restrictions on food commodities with regards to stocking, movement or exports, said Ramesh Chand.

HARISH DAMODARAN: As you say, the scarcity of the past is over. Is it time now to scrap the Essential Commodities Act (ECA), export controls and other restrictions that are clearly anti-farmer?

The farmer is a consumer too. But I agree, the sector’s interest today lies in scrapping these restrictions. In the last (June 15) meeting of the NITI Aayog’s Governing Council, we proposed some reforms, including on the ECA, APMC (agricultural produce market committee) reforms and enabling contract farming. The Prime Minister announced that a high-power committee of chief ministers would be constituted to examine these reforms. In 2016, the Union government passed an order, after which there are no real restrictions on food commodities with regards to stocking, movement or exports. But people say that a similar order was issued in 2002, but when prices increased in 2006, the controls were brought back. So they believe that unless the Act changes, the government will always find ways to bring back control if things are seen as going against the consumer. The NITI Aayog has suggested a way out — classifying commodities into two categories: foodstuffs and others. There are some commodities such as drugs where the ECA is needed, but not in case of agri produce. If the ECA has to be used, let us clearly define the conditions. If, say, there is a 20% decline in production because of natural calamity of an extraordinary order, or a war, only then can the provisions be brought back.

RAVISH TIWARI: How do you deal with political opposition to these reforms being suggested?

The supply situation is much better than in the past. The need for ECA to stop hoarding or black marketing does not arise in the case of most commodities, where even exports are happening. When we meet politicians, we give them examples by asking them if they ever felt the need to have ECA on eggs or milk (which are non-perishable and cannot be hoarded). Price volatility may be extreme in onions, but not in most other commodities. The best way to address volatility is through buffer stocks, not by ECA. Recently, West Bengal, for example, imposed movement controls in potatoes under ECA, but that only did a lot of harm to its farmers. Today’s India and its agriculture situation are very different.

Caricature of Ramesh Chand. (Illustration: Unny)

Caricature of Ramesh Chand. (Illustration: Unny)

PRABHUDATTA MISHRA: How does the NITI Aayog plan to make MSP more effective on the ground?

Everybody wants only the Centre to act. But agriculture is a state subject. It can only be the joint responsibility of the Centre and the states. The total production of all commodities where MSPs exist will be about 300 million tonnes. If the Centre is taking care of rice and wheat, whose production is about 200 million tonnes, can’t all the states combined take care of the remaining one-third production? Under PM-AASHA (Pradhan Mantri Annadata Aay Sanrakshan Abhiyan), states were given the option to implement MSP by procuring up to 30 per cent of the produce (similar to what the Centre is doing for rice and wheat). If in the process of procurement and disposal, the states incurred a loss, the Centre would bear it up to 30-35%. But the states did this only at a very small level. When the financial cost is being borne by the Central government, the states should come forward and take advantage of PM-AASHA by putting in place a procurement mechanism.

HARISH DAMODARAN: But instead of physical procurement, why can’t we have direct benefit transfer and simply pay the difference between MSP and market prices into farmers’ accounts?

The NITI Aayog has suggested this as well. If you take the MSP of wheat today, it is actually 30% higher than the international price. So if you procure wheat at MSP, you will only distort the market and exports will be hit, as domestic price is very high. Stocks, too, will pile. Direct benefit transfer is a very good idea and under PM-AASHA, we have the option of physical procurement as well as provision of deficiency price payments. In this case, we don’t have to look at the price received by each and every farmer. Farmers just have to register the area they are sowing under different crops before the season’s start on a portal. For every state, the harvest season is defined. So, at the end of the season, we monitor the actual price received by farmers in every district. Every district has 3-4 mandis. We take the average price at these mandis for the produce of Fair Average Quality. If that price is lower than the MSP, the difference can be paid for the area that has been reported by the farmer on the portal and taking the average yield for the crop in the district. I think the Madhya Pradesh government’s Bhavantar programme, despite the criticism it faced from some economists, was a good initiative. Today, the Food Corporation of India incurs a cost of Rs 700-800 per quintal in the process of paying Rs 1,600 as MSP to farmers. That can be avoided through direct payment of the price difference.

PRASANTA SAHU: Following the implementation of PM-KISAN, should the government now use this scheme to replace fertiliser and other input subsidies to farmers?

Income support and subsidies are two different things. PM-KISAN is the former. Subsidy was originally meant to promote the use of a particular input to ensure increase in productivity. When Dr C Rangarajan was the chairman of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (2009-2014), he asked me to find out the impact on the country’s food security and agriculture production if fertiliser subsidy was completely withdrawn and it was sold at market price. At that time, I calculated that if we do it suddenly in a knee-jerk manner, there will be 10% decline in foodgrain production. I look at PM-KISAN in a different way. It was brought in as some sort of income support, as crop prices remained low, and farmers in many places could not get the MSP. Subsidies are a different issue and they exist in many countries. We must try to make subsidies more efficient than they currently are. Subsidies in water and power are serious issues and must be addressed. Agricultural power subsidy for the country as a whole is about Rs 1 lakh crore. We did calculations to find how many irrigations a farmer would apply in case he is charged for power or if he is not charged anything. They will use 40% less irrigation on paddy alone if power is fully priced. Also in most cases, the yield will not fall.

According to Ramesh Chand, it is not proper to use agriculture and rural synonymously today.

According to Ramesh Chand, it is not proper to use agriculture and rural synonymously today.

SANDEEP SINGH: Rural consumption is slowing down. The government had talked of doubling farmers’ income. Where are we on that?

It is not proper to use agriculture and rural synonymously today. In rural India, only one-third of the income now comes from agriculture and two-third from non-agricultural activities. The last five years have been unique. For the first time in 65 to 70 years, we have had five consecutive years of less than average rainfall and the current one could even be the sixth. But Despite that, the annual growth rate of the value added in agriculture has been 2.9%, which is not bad. If growth rate becomes 5%, prices will crash and farmer incomes may decline by 30-40%. The slowdown in rural demand may be due to many reasons. One of it could be that loan waivers have reduced the flow of bank credit to rural areas. Industry people were happy when rural demand was good. But much of this demand was debt-based, with people taking loans to buy commodities. But families don’t have internal income to buy resources. As far as agriculture is concerned, for doubling farmers’ income, you need it to rise by over 10% every year. In the last three years, the growth rate, according to my calculation, has been 6%. We can still achieve the target if we are able to do something to prices. If farmers get 10% more than what they are getting, the income elasticity with respect to price would be 1.6. Then, farmer’s incomes will increase by 16%.

RAVISH TIWARI: How can we improve the current level of private and public investment in the agriculture sector?

If you look at public investment in agriculture as percentage of the GDP, the latest available data for 2016-17 shows it at 2.35%. For most of the recent period, it was 3%. Almost 85% of public investment in agriculture comes from the states. The Centre invests about 15% and that includes investment on irrigation and agriculture technology. Within private investment, the bulk of it comes from farmers themselves. If investment has to go up, that should now come from the corporate sector, which is currently very low. That is why the Prime Minister said last week in Parliament that corporates should not only see investments in agriculture in terms of making and selling tractors. They should make investments in agriculture, including in backend extension and working directly with farmers. This government wants to create an enabling environment for corporates to invest in agriculture. That will also require making changes in the regulatory environment, particularly facilitating contract farming.

RAVISH TIWARI: The private sector can invest in technology. But given the kind of protests against GM technology, how can the private sector be confident about investing?

GM technology is not the only technology through which countries have made progress in agriculture. There is public sensitivity about GM technology. But the biggest damage was done when Jairam Ramesh (former environment minister) took the issue of whether GM technology should be adopted to the streets and not leaving it to be decided by an expert body. On GM crops, the NITI Aayog’s stance has been — there should not be a blanket ban on the technology. It should not be encouraged in areas where we are able to get success through conventional means. The other thing that we emphasised was to finance public sector research in GM technology in a big way. This was mainly to allay the fears of people that private sector developers were charging hefty royalty. Some of our public sector research institutions were very close to developing a GM chickpea. Moreover, there are many more opportunities for the private sector other than GM. That includes GE or gene editing, which is different from modification (through introduction of alien genes).

RAVISH TIWARI: Cattle trade rules enforced two years back disrupted the market. Do such rules help farmers or create trouble for them?

The livestock sector grew by more than 6% in the last five years. If there were so many problems, it would not have been growing so fast. On the other hand, the crop sector, particularly cereal, oilseeds and pulses, is growing at just around 1.15%. This is why the overall agricultural growth rate comes down to 2.9%. But on the whole, I would say that Indian agriculture has now reached a stage where more the intervention by government, the lower will be the growth. The more the sector is liberalised, the higher will be the growth rate.